"The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.” — Ursula K. Le Guin

I love it when someone starts a sentence with, “No offense.”

It registers as permission—an invitation to return the favor, to share an idea or story that might change their reality forever.

After a radically hopeful keynote I gave last week about the future of leadership, an older gentleman approached me. He introduced himself as Ernie—late seventies, white-haired, bespectacled, with deep lines etched across his pensive face. Lines that declared decades of watching the world shift in both expected and extraordinary ways. His shoulders slumped slightly as if carrying the weight of history, but his sharp eyes betrayed a rebellious curiosity.

“No offense,” he said, adjusting his glasses, “but your ideas are unrealistic.”

I smiled, tilting my head. “How so, Ernie?”

“Leadership is regressing,” he explained, his voice constrained by resignation.

I leaned forward. “Tell me more…”

He let out a labored sigh. And then proceeded to rattle off the names of notorious presidents, prime ministers, and executives—figures he believed proved that society was stuck in old patterns of fear, greed, and exploitation. “Hamza, I don’t see how we get from this world to the one you showed us.”

I nodded, then gently clasped Ernie’s hands in mine.

“Less than 100 years ago, an eight-hour workday seemed impossible. So how do you think we got here, Ernie?”

He hesitated. “Henry Ford?”

I slowly shook my head. “That’s a convenient lie. Have you heard of The Haymarket Affair?”

“No,” he admitted.

"If I tell you about it, there's no going back. Okay?"

Ernie’s hands trembled, but he nodded.

May 3, 1886.

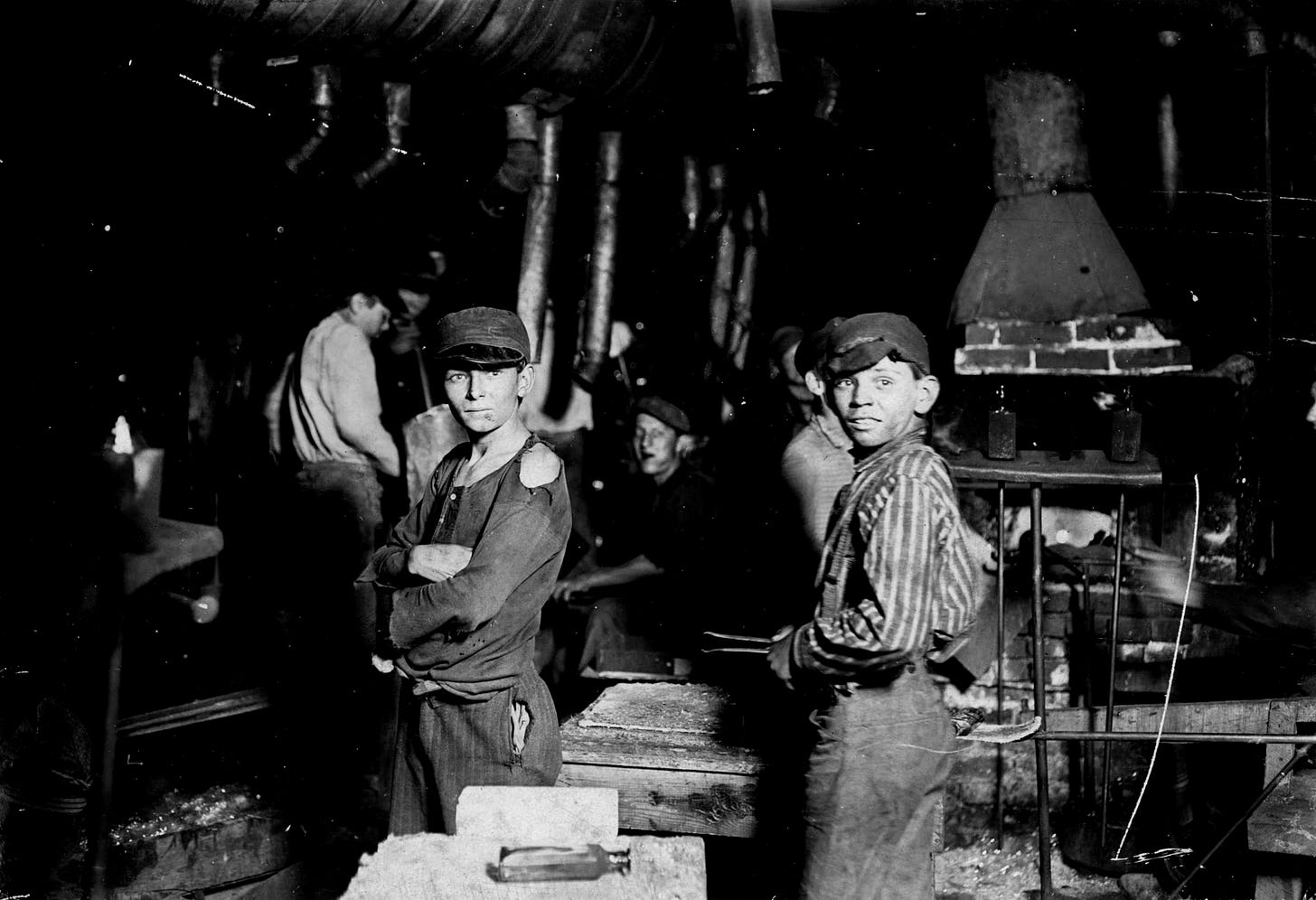

Chicago was restless. The Industrial Revolution was in overdrive—machines roared, smokestacks choked the sky, and the relentless menace of managerial directives dictated the rhythm of daily existence.

Workers toiled for 16 hours a day, six days a week, in suffocating conditions. Entire families—mothers, fathers, and even children as young as six—worked shoulder to shoulder, devoured in the maw of production—bodies exhausted, dreams abandoned. Factory floors were overcrowded, the air thick with soot, the mechanical monotony deafening. Accidents were common. Deaths even more so.

Ernie listened, nodding cautiously. “I suppose things were pretty bleak back then.”

“An understatement,” I replied. “In the name of profits, our lives became expendable resources. But the oppression was omnipresent. An entire system of control—media, government, industrialists, and law enforcement—colluded to maintain the status quo.”

Ernie's brow furrowed deeper with each word I spoke, his lips pressing into a tight, skeptical line.

“And this is far from a conspiracy theory, Ernie. Everything I’m sharing with you has been rigorously researched and extensively documented.”

I explained how politicians passed laws favoring industrialists, how the media spun tales of the ‘Great Man’ of history, crediting society’s progress to a systematically positioned few while turning workers’ struggles into cautionary tales, and how the army and police stood guard—not to protect people but property.

And then there was rampant xenophobia. The perfect weapon. Immigrant workers were pitted against local-born laborers. Fear and distrust fractured communities, turning potential allies into enemies.

“Divide and conquer,” Ernie muttered. “Feels familiar.”

An angry hush settled over the city as the sun dipped below the smoky skyline of May 3, 1886. The workers had finished waiting. After decades of toil in a system meant to dehumanize, they demanded something radical: an eight-hour workday. Just eight hours to work, eight hours to rest, and eight hours to live.

May 4, 1886.

Haymarket Square was spirited. Thousands stood together, and voices rose in unity. It was a peaceful but provocative protest fueled by incendiary speeches that ignited hope and tension in the crowd.

Then the bomb exploded.

Gunfire cracked through the air. Screams rang out as workers fell—some never to rise again.

And just like that, our world changed.

The system’s response? Suppression.

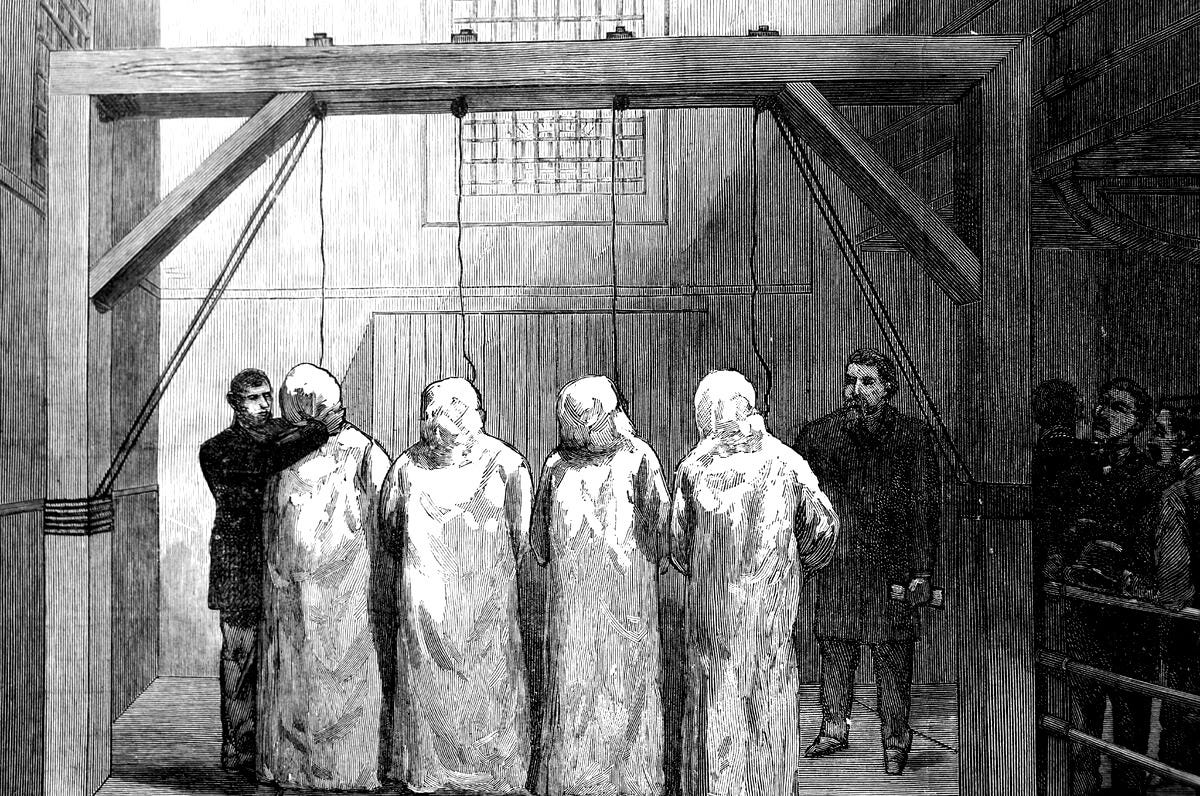

Workers were branded radicals. The media called them anarchists. Fear spread like The Great Chicago Fire and turned neighbor against neighbor. And when propaganda wasn’t enough, the system resorted to violence. Movement leaders were rounded up—scapegoated, imprisoned, and executed…including U.S. citizens.

But the idea of an eight-hour workday endured. Because it had to. Because people—when given the space to imagine a better world—will always reach for it.

Even among the ruins.

The legacy of The Haymarket Affair was so profound that the U.S. government sought to erase its revolutionary spirit from public memory. President Grover Cleveland strategically moved International Workers' Day from May to September to weaken its influence, stripping it of its radical roots and repackaging it as a harmless, apolitical celebration—Labor Day. What was once a powerful symbol of resistance and solidarity was rebranded into a day of parades and barbecues, severing it from the working class struggle that defined it.

And if you don’t know, now you know…

Ernie and I stared at each other in disquieting silence.

“Ernie, the eight-hour workday wasn’t a gift from a benevolent industrialist,” I said. “It was wrestled from the hands of those in power by generations of workers who fought, bled, and died for it. Ford merely co-opted it decades later to serve his own efficiency goals.”

Exasperation crept into Ernie’s voice. “But look around today, Hamza. The same kind of men are still in charge.”

“That’s the Apex Fallacy,” I countered. “You’re focusing on the people at the top and assuming they represent the whole—but they don’t. They’re just the most visible and the loudest.”

Every second we spend fixating on the flaws and failures of self-serving leaders amplifies their influence. But if we shifted our focus and invested in each other—by building inclusive communities, supporting co-creative ideas, and amplifying harmonious voices that reflect the world we want—we could create real change.

Observing Ernie’s diminishing frustration, I was reminded of something I shared during last year’s United Nations Science Summit:

"Leadership as we know it is dead. Presidents, chairmen, and CEOs—the idea that one person can co-create solutions for the many has reached its end."

These figures clinging to power today are relics of a bygone era. They are the final gasps of an old paradigm, gasping for relevance.

Today, it's easy to believe we're stuck and that things will never change. But the history of labor tells a radically different story. Every impactful change—including the eight-hour workday—didn’t happen because of one person, let alone a leader of a system designed to dehumanize.

It happened because of us. Leaders cannot exist without followers.

A man who thinks he leads but has no followers is simply a man taking a walk.

Change doesn’t happen because the system permits it.

It happens because the people see it.

It happens because the people believe it.

It happens because the people demand it.

“No offense,” I told Ernie, “The future isn’t waiting. If history has taught us anything, it’s that if we want something new, we’ll have to stop doing something old.”

"We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable—but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings." — Ursula K. Le Guin